NORTH ADAMS, Mass. — Without light, we couldn’t see the world. If there were no sun, the world would be in constant darkness, and, despite our eyes, everything would be invisible. This obvious point is a crucial one for artists, scientists and philosophers exploring the limits of visual perception.

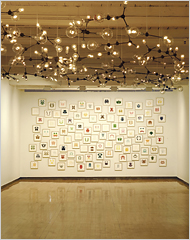

With “102 Colors From My Dreams” (2002), on wall, Spencer Finch seeks subconscious boundaries.

In “What Time Is It on the Sun?” Spencer Finch takes viewers on a journey — equal parts psycho-autobiography, travel log and science experiment — to demonstrate that even with light and eyes, vision doesn’t give you unmediated access to the world.

Because he often uses light and color as his primary tools, it’s easy to place Mr. Finch among artists like James Turrell and Olafur Eliasson. But while Mr. Turrell’s goal is to illuminate light’s transcendent qualities, and Mr. Eliasson’s is to emphasize humanity’s place in nature’s construction, Mr. Finch wants to replicate, through scientific means, his experience of light and color in a specific place and at a specific time.

The manner in which Mr. Finch presents his experiences shares the New England pragmatism of the late-19th-century psychologist and philosopher William James: He explores the world around him by experimenting with real (that is, his personal) sensory experience.

This gives some of his art a psychological veneer. One group of pastels, each a different shade of gray, represents the varying color of the ceiling in Sigmund Freud’s examination room in Vienna. As an “en plein air” experiment, the artist spent an entire day lying on the couch, recording the ceiling’s color as the light changed.

Another set of Rorschach-style ink drawings, 102 to be exact, represents colors the artist says he has seen in his dreams. He embarked on the experiment to see if by creating these images, he could intervene in the workings of his subconscious by capturing its perceptual limits.

Mr. Finch is at his best when both the art and the science in his work embrace the poetic, as they do, literally, in “Peripheral Error (After Moritake).” These watercolors, exquisite small spots of jewel-like colors on otherwise large, blank sheets of paper, portray a butterfly — not head on, but out of the corner of the artist’s eye. The series pays homage to a haiku by the Japanese poet Moritake:

The falling flower

I saw drift back to the branch

was a butterfly

Often the work promises poetry but doesn’t deliver it, as in “Two Hours, Two Minutes, Two Seconds (Wind at Walden Pond, March 12, 2007),” a bank of ordinary white window fans stacked on top of one anther. Arranged in a semicircle, the fans emit a steady breeze and an occasional gust over the time period specified by the work’s title. Mr. Finch experienced and measured these winds, using a weathervane and an anemometer, at the famous pond. It’s an interesting idea that falls flat in realization.

“Sunlight in an Empty Room (Passing Cloud for Emily Dickinson, Amherst, MA, August 28, 2004),” which recreates a moment in that visionary poet’s garden, also veers toward the overly clinical. Mr. Finch used a colorimeter — a device that measures the density of a color — to record the light in Dickinson’s garden. To replicate it, he created a bank of fluorescent lights and a large cloudlike form made of blue, purple and gray lighting filters. As you circumambulate the cloud, you should feel as if you are walking in her yard.

As you might expect, the light, while pristine, is cold. The installation does, however, succeed in testing the limits of visual perception by demonstrating that you need to feel the heat, smell the grass and hear the birds and insects to replicate the garden experience. The senses, in other words, do not stand alone.

Mr. Finch’s exhibition creates the impression that he, like James, Thoreau and Dickinson, is searching for the key with which to unlock the nature of existence. This is especially obvious in “Untitled (Only the Hand That Erases Writes the True Thing),” a series of photographs whose title refers to a quotation from the medieval Christian mystic Meister Ekhardt.

The images depict the buildings of the Swedish Parliament, just before and during a rainstorm. As the storm clouds reach the lake in front of Parliament, the buildings’ reflection becomes distorted and illegible — or erased — suggesting that truth is not found through science alone.