STEVE MUMFORD

The Snow Leopard

October 19 - November 23, 2013

Known for his drawings from the war zones of Iraq and Afghanistan, Steve Mumford was commissioned by Harper's Magazine to go

to Guantanamo. He made two trips in February and May 2013. Current issue of Harper's includes a portfolio of his drawings

along with Lawrence Douglas' cover story A Kangaroo in Obama's Court.

Steve Mumford:

I traveled to Guantanamo Naval Base for the first time last winter, to illustrate a story for Harper's Magazine on the military

trial of al Nashiri, accused of leading the attack on the USS Cole, and tortured many times under US custody.

Nashiri, quiet and wearing an unassuming white tee shirt was hardly noticeable as I drew the scene through the multiple sealed

panes of security glass in the media area at the far rear of the large, bland courtroom. More striking were the overhead TV screens

and audio of the same scene, on a 40 second delay, a disorienting counterpart to the live scene in front of us, a perfect

embodiment of the secrecy and paranoia embedded within Gitmo's culture.

The hearings lasted a day and a half, before getting sidelined in delays; with several days left, I poked around the sprawling

US-administered piece of Cuba with my escort from the Public Affairs Office, looking for compelling things to draw.

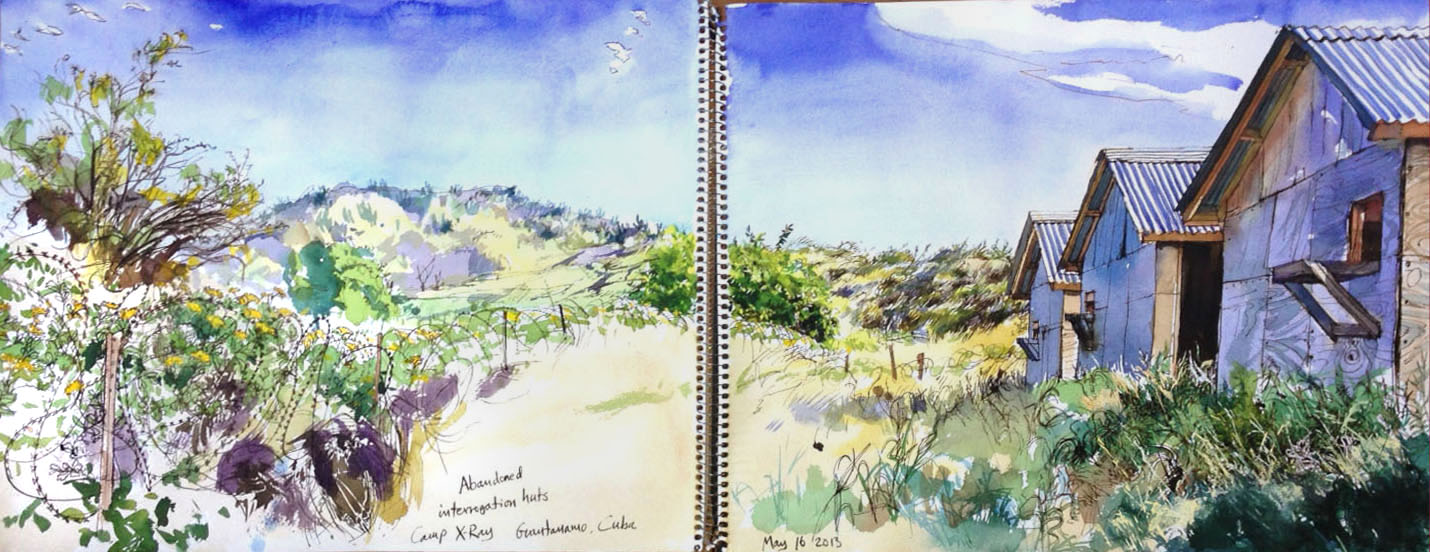

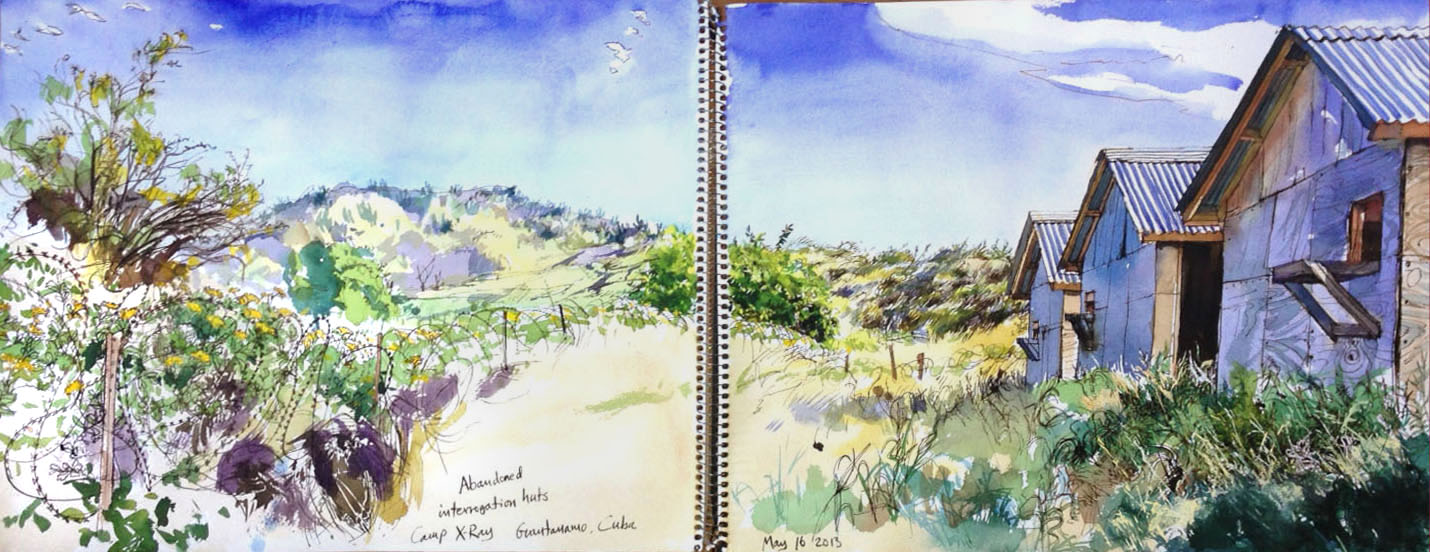

I found my subject in Camp X-Ray, a hauntingly beautiful ruin of a simple prison camp, hastily-erected on a scrubby, deserted

windswept plain overlooked by a ridge of distant hills. I could see the guard towers of the Cuban border following that ridge,

looking down at us.

X-Ray was built in a hurry and consists of nothing more than chainlink fencing, razor wire and a few plywood huts and guard towers.

Abandoned for a decade, nature has taken over: the fencing and razor wire is covered in vines, many of which were in flower on my

2nd visit. Tall wild grasses have spread throughout the grounds, and huge iguanas and banana rats have made X-Ray their home.

At one edge of the camp sit a few forlorn wooden huts, slowly settling into the earth. Their plywood floors are strewn with droppings

and vines are crowding in. These are where the CIA applied their enhanced interrogation techniques to the newly arrived prisoners

from Afghanistan. The wind constantly whistles through these empty, sun-soaked haunted spaces.

The prisons where the last 166 detainees are being held are small, high-security fortresses, their design and detail impregnable

and generic. It was in one of these where a sergeant of the MP unit in charge of the prison incredulously informed me that there was

no way that I would be able to see, let alone draw any of the detainees, even though this had been the stated purpose of the trip

and agreed to by the Public Affairs Unit.

For two days I drew the interiors of the facility as well as the MPs assigned to me, while they lounged on the bolted-down prison

chairs and chatted. Then word would be passed down that a detainee was being moved from somewhere to somewhere else, and I would be

hastily escorted to another part of the prison to draw until the danger of us seeing one another was over.

I drew everything associated with the prisoners but the prisoners themselves. I even drew a dim hallway echoing with the strains of

an early morning call to prayer, as the prisoners crouched in their cells a few feet away, but behind thick steel doors.

I only once caught a glimpse of some detainees, when a cord snapped, the wind blew some fabric away from a fence and I saw,

momentarily, magically, a few distant figures, lean in white tee shirts playing soccer. Then they were gone.

The subject of my Gitmo drawings is the very thing never pictured. And then the subject becomes the reason why they aren't there.

I was reminded of a passage from Peter Matthiessen's classic travel memoir about expectation, ambition and self. Matthiessen

desperately wants to see the animal he's journeyed so far to write about, but is destined to never see. His Zen teacher tells him

before he leaves, Expect nothing.

It doesn't exactly work and yet it does.